The Dogon Tribe and Sirius: Impossible Star Knowledge

By Howard Callahan, Ufologist

Picture this: a remote African tribe, living in mud homes tucked into the cliffs of Mali, somehow possesses detailed knowledge about an invisible star that Western astronomers only discovered in the 1970s using sophisticated telescopes. They know its orbit takes 50 years, understand it's made of super-dense matter not found on Earth, and celebrate its movements in elaborate ceremonies.

Sound impossible? Many scientists think so too. Yet this apparent contradiction sits at the heart of what's become known as "The Sirius Mystery" – one of anthropology's most persistent and controversial puzzles.

Hidden Knowledge in Mali's Cliff Dwellings

The Bandiagara Escarpment in Mali rises dramatically from the surrounding plains – a 500-meter high, 150-kilometer long sandstone cliff that appears almost like a natural fortress. Within this forbidding landscape lives the Dogon tribe, a people whose cultural practices have fascinated researchers for nearly a century.

The Dogon didn't choose this difficult terrain by accident. Historical evidence suggests they migrated here sometime between the 13th and 15th centuries, deliberately seeking an isolated home where they could preserve their culture and religious practices. Some scholars believe they were fleeing forced conversion to Islam, while others trace possible connections to ancient Egypt through linguistic and religious parallels.

"The cliffs became our protector," explained a Dogon elder to French anthropologists in the 1930s. "Here we keep our ways without disturbance."

This isolation created the perfect conditions for cultural preservation. The Dogon developed a distinctive society led by a spiritual-political figure called the Hogon – an elder selected from the dominant lineage who undergoes a rigorous six-month initiation period. During this time, he cannot shave or wash, must wear white clothes, and is cared for by a young virgin who prepares his meals but returns to her home at night.

The Dogon's architectural ingenuity mirrors their social complexity. Their mud-brick settlements feature male and female granaries for storing millet and personal possessions, low-roofed toguna meeting places where men gather to discuss village affairs (built deliberately low to prevent standing during heated arguments), and separate houses where menstruating women must stay for five days, considered ritually unclean.

But while these cultural practices might be expected in a traditional African society, what truly sets the Dogon apart is their apparent astronomical knowledge—information they simply shouldn't possess.

The Star That Shouldn't Be Known

To understand why the Dogon's stellar knowledge is so remarkable, we need to familiarize ourselves with the Sirius star system itself.

Sirius A, often called the "Dog Star," shines as the brightest star in our night sky. Located just 8.6 light-years away, it's been a celestial beacon throughout human history, featured prominently in the astronomical traditions of Egyptians, Greeks, Chinese, and countless other cultures.

But it's Sirius B that creates the mystery. This white dwarf companion star – the collapsed remnant of a once-massive star that has exhausted its nuclear fuel – orbits Sirius A in a 50-year elliptical path. Despite being roughly the mass of our sun, Sirius B has shrunk to approximately the size of Earth, creating matter so dense that a teaspoonful would weigh about five tons.

The scientific discovery of Sirius B followed a methodical progression:

- In 1844, Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel first hypothesized its existence based on wobbles in Sirius A's movement

- In 1862, Alvan G. Clark first observed it through a telescope

- Only in 1970 was the first photograph of Sirius B captured

Here's the puzzle: the Dogon allegedly knew about Sirius B long before Western astronomers confirmed its existence.

Some researchers even claim the Dogon recognized a third star in the system – sometimes called Sirius C – which remains unconfirmed by modern astronomy, though a 1995 study by French researchers did suggest gravitational evidence for its possible existence.

Star Wisdom Carved in Wood and Sand

According to French anthropologists Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen, who studied the Dogon extensively between 1931 and 1956, the tribe possessed remarkably accurate information about the Sirius system, which they incorporated into their religious traditions and material culture.

The anthropologists documented that the Dogon called Sirius "Sigi Tolo" (Star of Sigui) and its companion "Po Tolo" (Digitaria star, named after a tiny grain). They reportedly knew:

- Sirius B orbits Sirius A in an elliptical path

- The orbital period is 50 years

- Sirius B rotates on its axis

- It is extremely dense, made of a metal called "sagala" not found on Earth

"The problem of knowing how, with no instruments at their disposal, men could know the movements and certain characteristics of virtually invisible stars has not been settled, nor even posed," wrote Griaule and Dieterlen in their 1950 paper.

The Dogon allegedly represented this astronomical knowledge in their artwork and ceremonies. Their 400-year-old iron statues, sand drawings, and wooden sculptures depicted the orbit of Sirius B. Every 60 years, they celebrated the Sigui ceremony, which roughly corresponds to the orbital period of Sirius B, passing knowledge from one generation to the next.

They also recognized Jupiter's four main moons and Saturn's rings – celestial features that should have been impossible to observe without telescopes. Their understanding of planetary orbits predated Copernican astronomy, as they correctly understood that Earth and other planets rotate on their axes and orbit the sun.

How could they know these things? The Dogon themselves had an explanation that would send shockwaves through Western anthropology.

The Day of the Fish: Visitors From Sirius

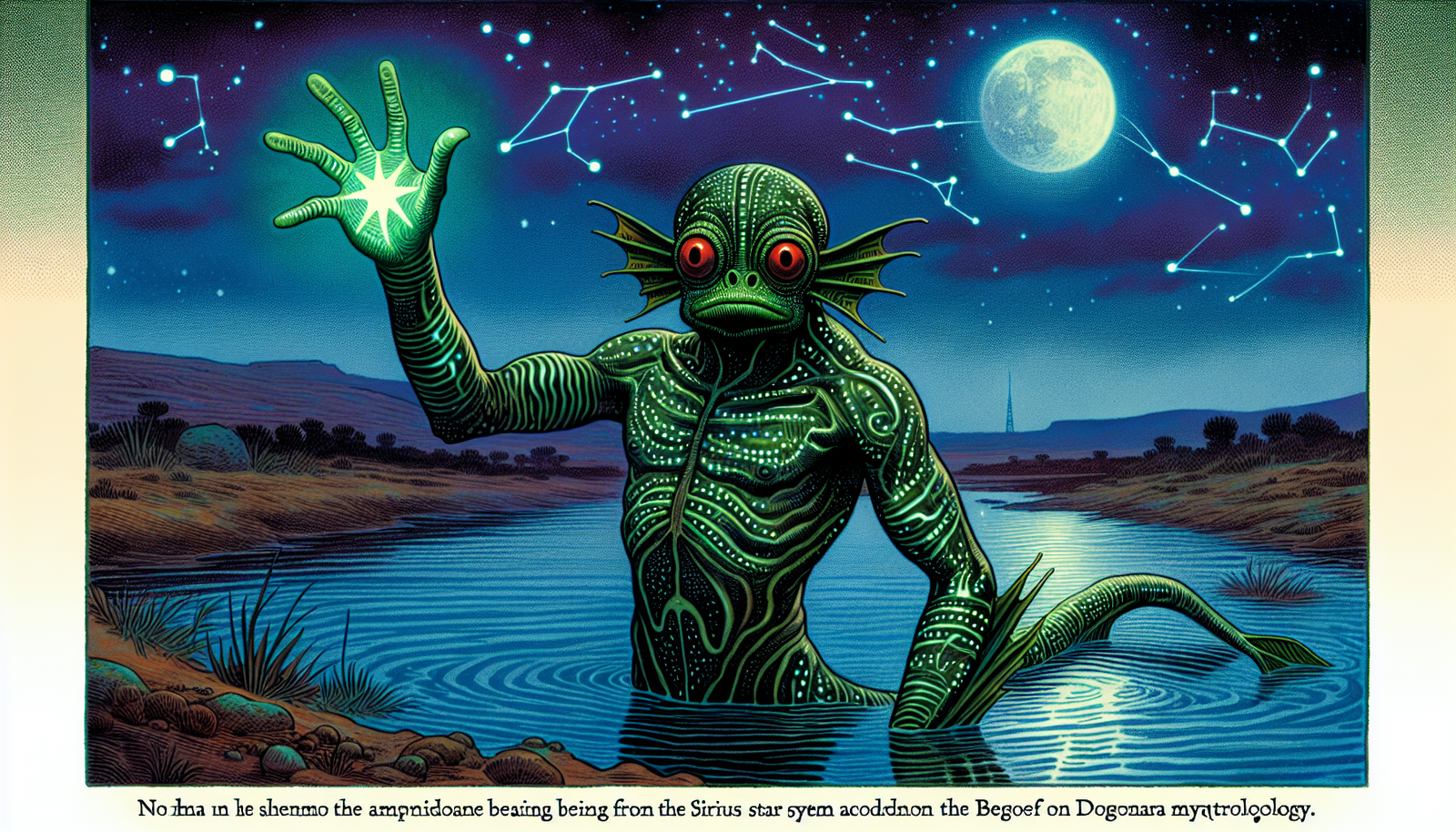

When asked about the source of their astronomical knowledge, the Dogon elders told Griaule a story that seemed pulled from science fiction. They claimed their ancestors were visited by amphibious beings from the Sirius system called the Nommo.

According to Dogon mythology, the Nommo arrived on Earth in an "ark" that made a spinning descent to the ground with great noise and wind, an event they called "The Day of the Fish." These beings had fish-like features – green skin covered with green hair, flexible unjointed arms, red eyes, and forked tongues. Their lower bodies were serpentine or fish-like.

The Dogon described the Nommo as hermaphrodites who taught their ancestors agriculture, weaving, and the secrets of the cosmos. They created detailed iron statues depicting these visitors, with artwork dating back centuries.

The Dogon weren't alone in their fish-deity traditions. Remarkably similar beings appear in the mythologies of numerous ancient cultures:

- The Babylonians described Oannes, a fish-man who emerged from the Persian Gulf to teach humanity civilization

- The Sumerians had Enki, a water god who brought wisdom and culture

- Greek mythology features Triton and various sea deities with fish or serpent tails

- Ancient Egyptian art from the Hellenistic period shows Isis and Osiris with entwined fish tails

- Chinese mythology depicts Fu Xi and Nü Wa, founders of civilization, with intertwined serpent tails

This cross-cultural pattern of amphibious teachers who bring knowledge from the stars raises fascinating questions about shared human experiences – or something more profound.

The Sirius Mystery Goes Public

The Dogon's star knowledge might have remained an obscure anthropological curiosity if not for Robert K.G. Temple's 1976 book "The Sirius Mystery." Temple, a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, brought the story to public attention, arguing that the Dogon's astronomical knowledge was evidence of contact with an advanced extraterrestrial civilization from the Sirius system.

Temple meticulously analyzed the Dogon's astronomical information, comparing it with modern scientific understanding. He expanded his investigation beyond Mali, tracing connections between the Dogon's knowledge and similar traditions in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Greece. The book became an international bestseller, bringing the Dogon's star wisdom to millions of readers.

One particularly intriguing detail Temple highlighted was what he called the "sacred fraction" – the ratio 253/246 = 1.053. This number, mentioned by ancient Greek writers, corresponds to the mass of Sirius B relative to our sun (1.053 solar masses). How could ancient peoples have known such a precise astronomical measurement?

Temple's book sparked intense debate. Mainstream scientists and anthropologists dismissed his extraterrestrial hypothesis, yet struggled to explain how the Dogon acquired their astronomical knowledge. Temple claimed that after publishing his book, he faced harassment from security agencies who considered extraterrestrial contact "the ultimate security issue."

In 1998, Temple published a revised edition with additional evidence, further fueling public fascination with the mystery. By then, the Dogon had become a popular destination for tourists seeking insight into their mysterious cosmic wisdom.

The Skeptics Respond

Not everyone was convinced by Temple's extraterrestrial explanation. Skeptics proposed alternative theories to explain the Dogon's astronomical knowledge.

The most straightforward explanation: cultural contamination. Skeptics suggested the Dogon acquired information about Sirius B through contact with Europeans before Griaule and Dieterlen's research. By the 1930s, details about Sirius B were available in astronomy books and popular science publications.

In 1893, a French astronomical expedition spent five weeks in Dogon territory observing a solar eclipse. This expedition, led by Henri-Alexandre Deslandres, could have shared information about Sirius that the Dogon integrated into their existing mythology.

Anthropologist Walter van Beek conducted a follow-up study of the Dogon in 1991, with results that directly contradicted Griaule's findings. Van Beek reported: "Though they do speak about Sigu Tolo [which is what Griaule claimed the Dogon called Sirius] they disagree completely with each other as to which star is meant... All agree, however, that they learned about the star from Griaule."

Examination of Griaule's field notes revealed potential methodological issues. The notes appeared to be a "haphazard collection of references to Dogon symbols and mythology without coherence or internal consistency," yet his published accounts presented a systematic revelation of astronomical knowledge.

Carl Sagan weighed in on the controversy in his 1979 book "Broca's Brain," noting inconsistencies in the Dogon's astronomical knowledge. If they had contact with an advanced civilization, why didn't they know about Uranus, Neptune, or Pluto? Why didn't they know Jupiter has more than four moons or that Saturn isn't the only planet with rings?

The debate highlighted fundamental questions about knowledge transmission, cultural interpretation, and the nature of traditional wisdom.

Exceptional Vision or Exceptional Visitors?

Between the extremes of cultural contamination and extraterrestrial contact lies a middle ground of possibilities that shouldn't be overlooked.

Some researchers have suggested that exceptional human vision could explain parts of the Dogon's astronomical knowledge. Under perfect viewing conditions, it might be possible for individuals with extraordinary eyesight to glimpse Jupiter's major moons or even detect a faint companion to Sirius. Traditional "dark eye" techniques, where observers allowed their eyes to fully adapt to darkness, might have enhanced their observational capabilities.

The Dogon might also have inherited astronomical knowledge from ancient Egypt. Their migration stories suggest connections to northeastern Africa, and linguistic analysis reveals similarities between Dogon terms and ancient Egyptian language. The Dogon supreme creator god, Amma, bears striking resemblance to the Egyptian god Amun.

The ancient Egyptians carefully observed Sirius (which they called Sopdet or Sothis) because its heliacal rising coincided with the annual flooding of the Nile. They built temples aligned to capture the light of Sirius on specific dates. Could the Dogon have preserved advanced Egyptian astronomical knowledge through oral tradition over centuries?

The story of the Dogon and their star knowledge continues to captivate our imagination precisely because it resists simple explanation. It challenges our assumptions about knowledge transmission in pre-literate societies and forces us to confront the limitations of our understanding of human history.

As we gaze up at Sirius twinkling in the night sky, the same star that captured the attention of the Dogon centuries ago, we're left with a profound mystery that bridges the gulf between ancient wisdom and modern science. Whether their knowledge came from extraordinary human observation, cultural diffusion from ancient civilizations, or something more exotic, the Dogon remind us that the universe contains wonders yet to be fully understood.

In the words of a Dogon elder: "The stars hold secrets for those who know how to listen."

From Bigfoot to UFOs: Hangar 1 Publishing Has You Covered!

Explore Untold Stories: Venture into the world of UFOs, cryptids, Bigfoot, and beyond. Every story is a journey into the extraordinary.

Immersive Book Technology: Experience real videos, sights, and sounds within our books. Its not just reading; its an adventure.