Uncovering the Bili Ape: Unmasking Congo's Colossal Chimpanzee Culture

By Oliver Bennett, Bigfoot Researcher and Teacher

The Allure of the Unknown

In the realm of primatology, few prospects are as tantalizing as the possibility of an undiscovered great ape species hiding in some far-flung wilderness. It's the stuff of legends - a real-life King Kong waiting to be found. As a lifelong student of both natural history and mythology, I've always been captivated by these tales of mystery beasts at the edges of the map.

So in 2003, when sensational reports began to emerge about a population of enormous chimpanzees rampaging through the war-torn jungles of the Democratic Republic of Congo, you can imagine my excitement. These "Bili apes", as they came to be known, were said to be larger, more aggressive, and more prolific tool-users than any known chimp population. Some eyewitness accounts even claimed they looked and acted more like gorillas, or some gorilla-chimp hybrid never before seen by science.

Could it be true? Was there really a lost megafauna of chimps thriving in the Congo Basin, as spectacular and significant a find as the okapi or mountain gorilla? I had to know more. And so began my own journey into the heart of Africa to unravel the mystery of the Bili apes.

A Century of Rumors

The legend of the Bili apes, I soon discovered, was nothing new. Strange stories about the giant chimpanzees of northern Congo had been circulating for over a hundred years, ever since the first European colonists and explorers began penetrating the region in the early 20th century.

In 1908, a Belgian army officer returned from the Congo with a collection of large ape skulls he said came from near the town of Bili. The skulls were unlike any known ape - bigger than a chimp's, but with the prominent brow ridge of a gorilla. At the time, gorillas had never been seen in that part of Africa. A perplexed curator at Belgium's Royal Museum for Central Africa catalogued the skulls as belonging to a new gorilla subspecies, but they were later reclassified as chimps and largely forgotten.

Whispers about the Bili apes persisted though, carried back from the Congo's wild hinterlands by hunters, explorers and missionaries. The Azande people who inhabit the region had long spoken of two distinct kinds of apes in the forest - the smaller "tree beaters" (normal chimps) and the much larger, more aggressive "lion killers" (the Bili apes).

Eyewitness reports described a fearsome creature that could grow up to 6 feet tall and weigh over 400 pounds - bigger than any chimp or gorilla on record. They slept on the ground in gorilla-like nests, and had a terrifying penchant for attacking lions, leopards, and elephants. Most bizarrely, locals claimed the Bili apes would gather in the hundreds to howl at the rising and setting moon - a behavior never before documented in apes.

Renewed Intrigue

Fast forward to the 1990s, and the Bili ape legend began to attract serious scientific interest. Swiss photographer and conservationist Karl Ammann, on assignment in Congo, became intrigued by the old stories and ape skulls in the museum collections. In 1996, he mounted an expedition to Bili to investigate.

What Ammann found there astonished him. Around Bili town, he collected accounts from hunters of recent encounters with huge, hyper-aggressive chimpanzees that didn't fear humans at all. They told him these apes were so powerful, even poisoned arrows couldn't bring them down.

Trekking into the forest, Ammann discovered the creatures' massive ground nests, 2-3 times larger than a typical chimp nest. He took photos of giant footprints in the mud, and measured an enormous dung pile far bigger than any chimp's. Most incredible was a photograph one of his trackers brought back of what appeared to be a freshly killed Bili ape - and it was the size of a gorilla.

Ammann, now convinced there was indeed an unknown ape species awaiting discovery, published his findings and called for a major research effort to solve the Bili ape mystery once and for all. The media went wild over the story, and interest in the Bili apes exploded worldwide.

Eyewitness Encounters

In 2002 and 2003, Ammann teamed up with primatologist Shelly Williams to launch a series of expeditions into the depths of the Bili Forest. Williams, armed with a camera trap and audio recorder, was determined to become the first scientist to make contact with the elusive Bili apes.

After weeks of grueling treks through the sweltering jungle and swamps, Williams finally hit pay dirt. Her small team was moving through a dense stand of trees when a curious sound made them freeze in their tracks - hooting calls that seemed to be coming from all around them. The apes, it seemed, had found them first.

Heart pounding, Williams readied her camera as the brush began to shake violently mere yards away. She expected the apes to flee at the sight of humans, like any normal chimp would. But what happened next would haunt her forever.

"We could hear them in the trees, about 10 meters away," Williams later recalled, "and four suddenly came rushing through the brush towards me. If this had been a mock charge they would have been screaming to intimidate us. These guys were quiet, and they were huge. They were coming in for the kill - but as soon as they saw my face they stopped and disappeared."

Shaken but exhilarated, Williams returned from her close encounter with a wealth of new observations about the Bili apes. She noted their large size, with some males appearing to be over 5 and a half feet tall. Their faces were flatter and more "human-like" than a typical chimp's, with a heavy brow ridge reminiscent of a gorilla. And, most strikingly, they had patches of gray fur over their entire bodies, rather than just on their backs like gorillas. It was this detail that led Williams to dub them "the gray ghosts of the forest."

Over the next few years, Williams and other researchers managed to habituate several of the Bili ape groups to their presence, allowing for dozens of hours of direct behavioral observations. They marveled at the apes' extensive tool use, including ant-dipping wands over 8 feet long, and watched in awe as 400-pound males erupted into fantastic charging displays, hurling rocks and beating their chests.

But the more they saw, the more questions arose. Examinations of the Bili apes' mitochondrial DNA, passed down from mother to offspring, clearly showed they were chimpanzees, not a new species. But then why did they look and act so differently from any known chimp population? Were they a new subspecies? Some kind of gorilla hybrid? Or was this astonishing variation in chimpanzee size, appearance, and behavior something that had been there all along, overlooked by science in the vastness of the Congo Basin?

A Chimpanzee Culture Revolution

In 2004, researcher Cleve Hicks launched the most ambitious study of the Bili apes to date. Over the next two years, Hicks and his Congolese assistants would log thousands of kilometers trekking through the Bili-Uere landscape, meticulously documenting every trace of chimpanzee behavior they could find.

Hicks focused his research on the Bili apes' most intriguing trait - their unique and complex culture. Like humans, chimpanzees are not blank slates, born with a fixed set of instinctive behaviors. Instead, they learn and pass on knowledge to their offspring, giving rise to cultural traditions that can differ greatly between populations.

As Hicks immersed himself in the world of the Bili apes, the astounding depth and diversity of their culture began to reveal itself. Perhaps most fascinating was their propensity for ground-nesting. All other known chimp populations spend their nights high up in the treetops, safe from leopards and other dangers below. But the Bili apes defiantly build their beds right on the forest floor, even when trees are readily available. Over 20% of the nests Hicks found were terrestrial, an unheard-of frequency for chimps.

The Bili apes are also the most prolific and innovative tool-users ever observed among chimpanzees. Everywhere Hicks went, he found evidence of their "material culture" - sticks and rocks modified for various purposes and passed down through the generations.

There were the giant ant-dipping wands, some over 8 feet long, that the chimps use to extract aggressive driver ants from their nests. Imagine the dexterity and patience required to handle such an unwieldy tool, carefully inserting it into the tiny holes of the ant nest without breaking it. No other chimp population is known to make such enormous, specialized ant-dipping tools.

Even more astonishing was the Bili apes' "smashing culture." Hicks found hundreds of rocks and logs that the chimps had used as anvils to crack open hard-shelled fruits and nuts. But the Bili apes took it a step further - they were using their anvils to smash open giant African land snails and even tortoises, something never before seen in chimps. Everywhere Hicks looked, it seemed, the Bili apes were dreaming up new ways to exploit their environment.

Perhaps most controversial are the persistent reports from locals that the Bili apes hunt and eat big cats. Hicks himself never witnessed a kill, but he did find a chimp feasting on a dead leopard, and saw scratch marks on trees consistent with a leopard being chased by apes. Could it be that these chimps have become so large and behaviorally flexible, they've turned the tables on one of their most feared predators?

The more Hicks uncovered about the Bili apes' way of life, the clearer it became - this was a chimpanzee population totally unique in its ecology and culture, adapted to the distinctive environment of the Congo Basin. And yet, for all their peculiarities, the Bili apes were undoubtedly still chimpanzees. Their DNA proved it.

Hicks now saw the Bili apes not as a new species or subspecies, but as a powerful testament to the remarkable behavioral plasticity of chimpanzees. Across Africa, chimp populations are known to vary widely in their traditions, from nut-cracking in the west to algae-scooping in the east. But the Bili apes represent something new - a chimp culture so distinctive, so revolutionary in its embrace of ground-dwelling and new foraging techniques, that it forces us to totally reimagine what's possible for these apes and perhaps for our earliest hominid ancestors as well.

In a sense, the Bili apes are to chimpanzees what human cultures like the Inuit or Yanomami are to us - populations that have adapted over millennia to thrive in extreme environments and preserve astonishing cultural diversity. And that, in my mind, makes them even more valuable than a new species. The Bili apes show us that culture isn't something that belongs only to humans - it's a primal inheritance we share with our closest relatives, and a force that can transform species from within.

An Uncertain Future

But will the Bili apes' singular way of life endure? For all the wonders Hicks revealed, his research also documented an ominous new threat to the apes' survival. As the DRC's long civil war ended and the Bili region became more accessible, a massive new bushmeat trade emerged almost overnight.

Suddenly, the forests the Bili apes had ruled for untold generations became hunting grounds for well-armed poachers seeking to feed the growing demand for ape meat in cities like Buta and Aketi. Between 2007-2008, Hicks and his team observed a staggering 34 orphaned chimp infants and 31 carcasses for sale in the region's markets, a rate of killing that could quickly decimate the population.

Even more troubling was the reason why so many of the Bili apes were winding up in cooking pots - their curious and fearless nature. The same naïve fascination with humans that allowed researchers like Hicks to habituate the apes was now making them easy targets for poachers.

"The Bili apes are in big trouble," Hicks told me grimly. "These chimpanzees have likely never encountered hunters before, so they don't flee like other chimps. Instead, they just sit and stare as the poacher walks right up and shoots them."

As if the bushmeat crisis wasn't enough, the Bili apes also face an unprecedented loss of habitat as industrial mining, logging, and agriculture penetrate into the heart of the Congo Basin for the first time. Without aggressive conservation action, it may only be a matter of time before one of the most behaviorally complex chimpanzee cultures on Earth is erased forever.

Preserving a Wonder

So what will it take to save the Bili apes? Hicks and other conservationists are now working to establish a new protected area for the apes, one that would encompass a staggering 11,803 square miles of pristine forest. But in an impoverished region plagued by instability, it's an uphill battle.

The first step, Hicks says, is to continue the research that will make the wider world care about the Bili apes' fate. "Right now, the chimps are seen by many people as just another source of meat," he explains. "We need to show that they're a priceless part of the Congo's natural heritage, as important as the mountain gorillas are in Rwanda. These apes have so much more to teach us."

Indeed, for all we've learned about the Bili apes since those first tantalizing rumors reached Karl Ammann's ears, there are still far more questions than answers. How far does the Bili ape culture extend? Do even more dramatic behavioral variations exist in the remotest corners of their range? And what other chimp populations are out there, awaiting discovery in the great green heart of Africa?

Most intriguing of all - could the Bili apes represent a glimpse not just into the world of chimpanzees, but into our own evolutionary past? For decades, researchers have speculated that the transition from forest to savanna may have been the key turning point that set our ancestors on the path to becoming human. They've envisioned the first hominids as creatures of the mosaic woodlands, using simple tools to exploit hard-to-reach foods and taking their first tentative steps toward a life on two legs.

Now, in the Bili apes, we may have found the closest thing to a living model of that pivotal moment in our history. Here is a chimpanzee society adapted to the very same environment that gave rise to us, a society that has pushed the limits of what was thought possible for apes not by speciating, but by innovating.

In a sense, that's even more astounding than discovering a new species - it's like looking into an evolutionary mirror and seeing not the end product, but the process itself unfolding. The Bili apes remind us that we are all creatures of culture, and that in the diversity of chimpanzee traditions we

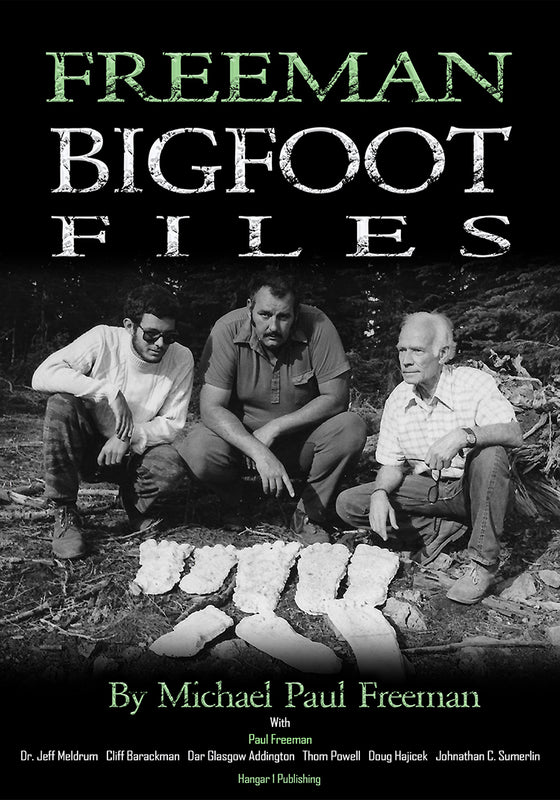

From Bigfoot to UFOs: Hangar 1 Publishing Has You Covered!

Explore Untold Stories: Venture into the world of UFOs, cryptids, Bigfoot, and beyond. Every story is a journey into the extraordinary.

Immersive Book Technology: Experience real videos, sights, and sounds within our books. Its not just reading; its an adventure.